The Coddling of the American Mind by Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt

How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure.

The three Great Untruths #

- The Untruth of Fragility: What doesn't kill you makes you weaker.

- The Untruth of Emotional Reasoning: Always trust your feelings.

- The Untruth of Us Versus Them: Life is a battle between good people and evil people.

The most interesting is how those untruths show up, how the authors prove them wrong and see examples of the harm they bring.

1. What doesn't kill... #

What does not kill me makes me stronger

— Friedrich Nietzsche

Most of the time, stress, and obstacles make us stronger. It's called Posttraumatic growth. There are exceptions of course, but I like how authors emphasized that original definition for trauma in PTSD moved from objective to a subjective standard. Trauma no longer needed to be objectively "outside the range of usual human experience."

From what I understood, exceptions can be:

- Trauma so strong that leaves you crippled (think of equivalents of losing your legs)

- Toxic and prolonged stress can negatively impact small children

Even if something terrible happened, the treatment is not to avoid it. I've heard a lot about the success of the Exposure Therapy. You slowly learn to ignore whatever triggers you.

2. Feelings #

"Nothing is miserable unless you think it so; and on the other hand, nothing brings happiness unless you are content with it."

― Boethius, The Consolation of Philosophy

When I look at Cognive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), it seems more like a practical philosophy and healthy way of thinking than a therapy. Even Greg and Jonathan write about CBT as Cognitive Behavioral Techniques that are useful even if you don't have depression or anxiety.

CBT is based on the belief that thought distortions and maladaptive behaviors play a role in the development and maintenance of psychological disorders.

CBT created a list of cognitive distortions, but the one that's the most relevant here is called emotional reasoning.

Emotional reasoning is a cognitive process by which a person concludes that his/her emotional reaction proves something is true, regardless of the observed evidence. For example, even though a spouse has shown only devotion, a person using emotional reasoning might conclude, "I know my spouse is being unfaithful because I feel jealous."

— Wikipedia emotional reasoning

Using your feelings to prove that something takes place is irrational. No one can invalidate your feelings, but the fact that you feel something doesn't prove anything.

One example is the concept of microaggressions.

Psychologist Derald Wing Sue defines microaggressions as "brief, everyday exchanges that send denigrating messages to certain individuals because of their group membership." The persons making the comments may be otherwise well-intentioned and unaware of the potential impact of their words.

— Wikipedia microaggressions

It can be useful as a concept in some cases. Unfortunately, to prove that someone was (micro)agressive you only need the interpretation of the receiver. There would be no objective analysis if something was intended to be harmful. Even worse microaggressions can be unintentional. It's designed to encourage emotional reasoning.

Another one is debunked in the articles in the Atlantic by

Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff Why It's a Bad Idea to Tell Students Words Are Violence. Or you can read why using stress to impose censorship is a flawed idea When Is Speech Violence and What's the Real Harm?

If it doesn't feel right, it probably isn't.

Jonathan and Gret label this statement an encouragement for emotional reasoning. Personally, I see the value in this sentence. I can agree that saying "probably" is too strong, but I would still stand behind something like "If it doesn't feel right, stop looking at your phone and look around to investigate."

3. Good and Bad #

If only there were evil people somewhere insidiously committing evil deeds, and it were necessary only to separate them from the rest of us and destroy them. But the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being. And who is willing to destroy a piece of his own heart?

— Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

Splitting or black-and-white thinking is another cognitive distortion that is part of our culture.

Splitting (also called black-and-white thinking or all-or-nothing thinking) is the failure in a person's thinking to bring together the dichotomy of both positive and negative qualities of the self and others into a cohesive, realistic whole. It is a common defense mechanism. The individual tends to think in extremes (i.e., an individual's actions and motivations are all good or all bad with no middle ground).

— Wikipedia Splitting

It can become dangerous if you consider how easy it is for humans to create groups, even based on arbitrary rules. What the authors warn us against are groups created with "common-enemy identity politics."

There has never been a more dramatic demonstration of the horrors of common-enemy identity politics than Adolf Hitler's use of Jews to unify and expand his Third Reich.

When we dehumanise and demonise our opponents, we abandon the possibility of peacefully resolving our differences, and seek to justify violence against them.

— Nelson Mandela

The better way is to build on top of the "common-humanity identity politics." Example of Martin Luther King Jr. is a good one. He emphasized that both black and white were Americans.

It seems similar to the shift that happened in the US in the attitude to gay marriage. Radically Normal: How Gay Rights Activists Changed The Minds Of Their Opponents. Of course it was based on common-humanity and drawing of the bigger circle around all the society not looking for anyone to blame or oppose.

Witch Hunts #

I want to quote from the book here. Unfortunately, I don't have access to the original paper A Durkheimian Theory of "Witch-Hunts" with the Chinese Cultural Revolution of 1966-1969 as an Example

by Albert James Bergesen.

I hope you will remember it next time you will see a "witch-hunt" on twitter/facebook or any other media or even real life.

Bergesen notes that there are three features common to most political witch hunts: they arise quickly, they involve charges of crimes against the collective, and the offenses that lead to charges are often trivial or fabricated. Here's how Bergesen puts it:

- They arise quickly: "Witch-hunts seem to appear in dramatic outbursts; they are not a regular feature of social life. A community seems to suddenly find itself infested with all sorts of subversive elements which pose a threat to the collectivity as a whole. Whether one thinks of the Reign of Terror during the French Revolution, the Stalinist Show Trials, or the McCarthy period in the United States, the phenomenon is the same: a community becomes intensely mobilized to rid itself of internal enemies."

- Crimes against the collective: "The various charges that appear during one of these witch-hunts involve accusations of crimes committed against the nation as a corporate whole. It is the whole of collective existence that is at stake; it is The Nation, The People, The Revolution, or The State which is being undermined and subverted."

- Charges are often trivial or fabricated" "These crimes and deviations seem to involve the most petty and insignificant behavioral acts which are somehow understood as crimes against the nation as a whole. In fact, one of the principal reasons we term these events 'which-hunts' is that innocent people are so often involved and falsely accused."

To Gergsens's list we'll add a fourth feature, which necessarily follows from the first three:- Fear of defending the accused: When a public accusation is made, many friends and bystanders know that the victim is innocent, but they are afraid to say anything. Anyone who comes to the defense of the accused is obstructing the enactment of a collective ritual. Siding with the accused is truly an offense against the group, and it will be treated as such. If passions and fears are intense enough, people will even testify against their friends and family members.

I've mentioned a couple of examples on my old blog when I first heard about this book. Take a look if you want to dig deeper SJW

6 Possible Reasons they propose #

- The Polarization Culture

- Anxiety and Depression

- Paranoid Parenting

- The Decline of Play

- The Bureaucracy of Safytism

- The Quest for Justice

The most interesting for me are the points related to the way we raise children and the quest for justice.

iGen #

I'm not entirely convinced that iGen is at fault. Even the way they were raised may not be so bad. Unfortunately, the rising rate of suicide convinced me that it's something worth mentioning here. The most straightforward one is to limit screen time.

When kids use screens for two hours of their leisure time per day or less, there is no elevated risk of depression. But above two hours per day; the risks grow larger with each additional hour of screen time.

Justice #

Intuitive justice is the combination of distributive justice (the perception that people are getting what is deserved) and procedural justice (the perception that the process by which things are distributed and rules are enforced is fair and trustworthy).

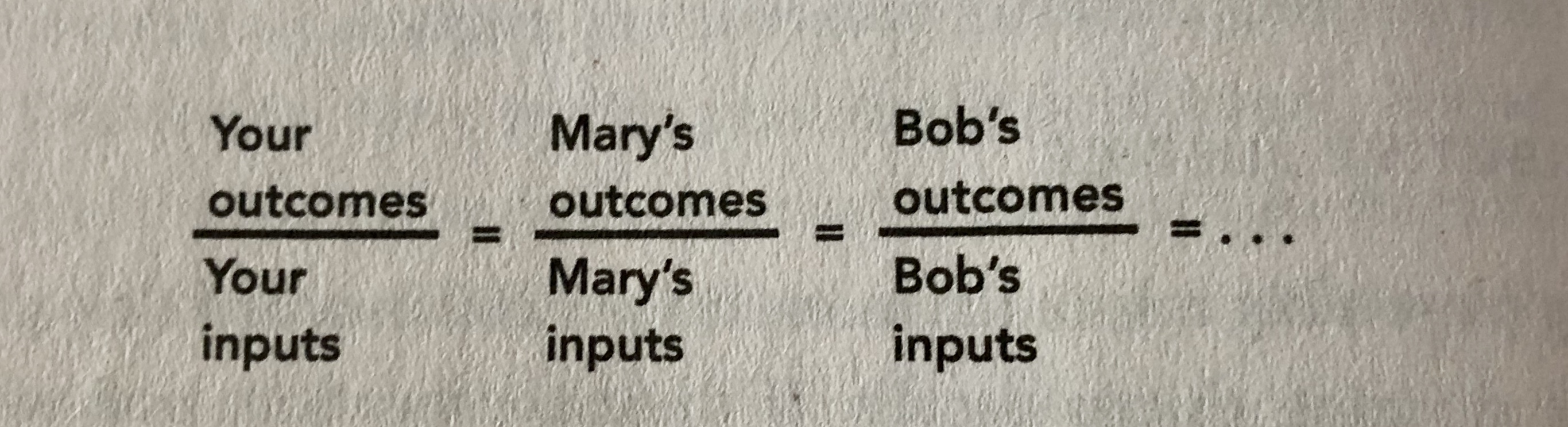

distributive + procedural = Intuitive justice

Distributive justice #

Distributive justice is best explained with an equation. Most of the time it's running in our head, maybe even unconsciously but it's worth to see it how it works.

You may see it during discussions about gender pay gap. If you earn less because you work four days a week, then it's ok. If you work five days a week and do the same amount of work but earn less because of your gender, tenure, or any other reason, then it will feel unjust. Please note that it will feel unjust for all involved not only the person that earns less.

Procedural justice #

People want to know that the process by which decisions are made is fair. They are even more likely to accept decisions that are harmful to them because of it. There are two aspects that influence us:

- How is the decision being made?

- How are people treated during the way?

That's likely why I think that public shaming is terrible. There is no presumption of innocence or any sort of just procedure to it. Even if there is some proof in some cases, people are treated so badly in the process that it's terrifying.

Equal-Outcomes Social Justice #

Personally, I can't call it justice as it often breaks both distributive and procedural justice.

The idea is simple and is motivated by good intentions. For example, we want to have 50% of women in tech, or you want to improve the admission rates of black students and minorities. The problem starts when you're too greedy about it, and you start to sacrifice fairness to achieve it. Looking, for example, I've noticed an article at BBC Harvard University 'discriminates against Asian-Americans'

but you can probably find more (and better) if you're interested.

How does it show up in IT? #

- GitHub's ElectronConf postponed because all the talks (selected through an unbiased, blind review process) were to be given by men.

- POINT: Postponement of SCA panel reveals snowflake culture

Compare it to How blind auditions help orchestras to eliminate gender bias

Questions and thoughts after reading the book #

- Are there any situations when emotions give us a good indicator of the situation? The book focuses on the idea from CBT that all emotions come from your thoughts. Many times your cognitive distortions lead to those emotions, but you have to be right at least sometimes?

- I wonder if your feeling of fear in the call-out culture is an example of emotional reasoning? What about other situations like feeling the company culture?

- I'm not convinced that iGen as a generation is the culprit. I've noticed the same things happening in the IT world with most of the involved being Millenials or older. What seems to be changing to me is a culture - not generations.

- I wonder if the limit of 2 hours of leisure screen time a day wouldn't be a good rule of thumb for grown-ups as well?

Want to learn more?

Sign up to get a digest of my articles and interesting links via email every month.